THREAT and ERROR Management (TEM)

- Ariarso Mahdi Hadinoto

- Jul 23, 2024

- 7 min read

Threat and error management (TEM) is a safety management approach that has been described as ‘simply an extension of the concept of airmanship.

It is the process of detecting and responding to threats (such as adverse weather) and errors (such as unclear communication between crew members) before they compromise safety. TEM aims to maintain safety margins by training pilots and flight crews to detect and respond to threats and errors that are part of everyday operations.

If not properly managed, these threats and errors have the potential to generate undesired aircraft states (UAS). The management of undesired aircraft states represents the last opportunity to avoid an unsafe outcome and thus to maintain safety margins in fight operations.

What is TEM?

TEM provides a way for pilots to look for potential threats to fight operations in a structured way. They actively manage these threats and any errors that may lead to undesired aircraft states and therefore to the safety of the fight. TEM encompasses training, briefings, checklists, standard operating procedures, and human factors principles for single-pilot and multi-crew operations.

Threat and error management:

Recognize and manage errors

Recognize and manage threats

Recognize and manage undesired

aircraft states

What is THREAT?

A threat is a situation or event that has the potential to have a negative effect on fight safety, or any influence that promotes an opportunity for pilot error/s.

Threats are generally external (such as bad weather) or internal (such as physiological and psychological state).

Threats such as fatigue increase the likelihood of errors, leading to degraded situational awareness and poor decision-making. Pilots need good situational awareness to anticipate, recognize, and manage threats as they occur.

External threats include:

adverse weather

weight and balance

passenger distraction

early starts and late finishes

night operations

reduced runway length

other traffic, high terrain, or obstacles

the condition of the aircraft.

Internal threats include:

fatigue

inexperience

over-or under-confidence

isolation

impulsiveness

lack of recency and proficiency

press-on-itis.

Managing Threats

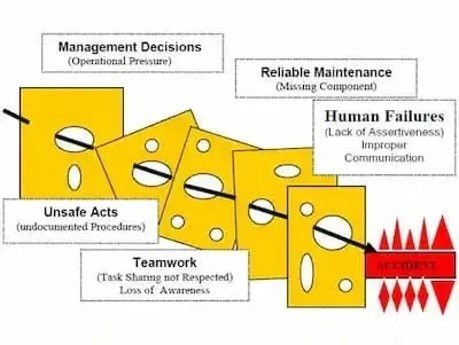

The TEM model includes three threat categories: anticipated, unanticipated, and latent. All three can reduce safety margins.

Latent threats may not be clear and may need to be uncovered by formal safety analysis and specifically addressed in your organization’s training and procedures.

ANTICIPATED

Some threats can be anticipated such as:

thunderstorms, icing, wind shear, and other forecast bad weather

congested airports and landing areas

wires and other obstacles

complex ATC clearances

cross and/or downwind approaches and landings

outside air temperature/density altitude extremes

aircraft mass and balance

UNANTICIPATED

These are other threats that can occur unexpectedly, suddenly, and without warning. Pilots must apply the skills and knowledge they have acquired through training and operational experience to deal with issues such as:

in-flight aircraft malfunctions

automation—anomalies and over-reliance

unforecast weather, turbulence, icing

ATC re-routing, unexpected congestion, non-standard phraseology, navigation aid unserviceability, confusion over similar call signs

ground handling

wires and other obstacles

unmanned aircraft systems (drones)

unforecast bird/wildlife activity

laser attacks

contaminated or sloping landing areas. Recast or known bird/wildlife activity.

LATENT THREAT

Some threats may not be directly obvious to, or observable by, pilots and may need to be discovered through formal safety analysis. These are considered latent threats and may include organizational weaknesses and the psychological and physiological state of the pilot. They include:

organizational culture

organizational change

incorrect or incomplete documentation, such as poor manuals

equipment design issues such as landing gear and fap levers located too close to each other, or inaccurate fuel gauges

operational pressures and delays, such as undue pressure to get a job done

perceptual illusions such as approaches to sloping runways

fatigue and rostering

lack of recent experience and proficiency

Stress

over-confidence or under-confidence.

ERROR

As humans we all make errors. In TEM, errors are defined as fight crew actions or inactions which lead to:

A deviation from crew or organizational intentions or expectations

Reduced safety margins

Increased probability of adverse operational events on the ground and during the fight.

Adverse operational events can be handling errors, procedural errors, or communications errors.

Errors can be the result of a momentary diversion of attention (slip), or memory failure (lapse) induced by an expected or unexpected threat. There are also more deliberate, intentional non-compliance errors. These are often shortcuts used to increase operational efficiency but in violation of standard operating procedures. Slips and lapses are failures in the execution of an intended action. Slips are actions that do not go as planned, while lapses are memory failures.

Mistakes are failures in the plan of action; even if the execution of the plan was correct, it would not have been possible to achieve the intended outcome.

While errors may be inevitable, we need to identify and manage them before safety margins are compromised. Typical errors in charter operations include:

Incorrect performance calculations (mistakes)

Inaccurate fight and fuel planning (slips, lapses)

Non-standard communication (mistakes, violations)

Aircraft mishandling (slips)

Incorrect systems operation or management (slips, lapses, mistakes)

Checklist errors (slips, lapses)

Failure to meet fight standards, such as poor airspeed control (slips)

Aircraft Handling Error

Flight control

Incorrect faps or power settings.

Ground navigation

Attempting to turn down the wrong taxiway/runway, missed

taxiway/runway/gate, failure to hold short.

Manual flying

Hand flying vertical, lateral, or speed deviations.

Systems/radio/instruments

Incorrect GPS, altimeter, fuel switch, transponder, or radio frequency

settings.

Procedural Errors

Briefings

Missed items in the brief, omitted departure, take-off, approach, or

handover briefing.

Callouts

Omitted take-off, descent, or approach callouts.

Checklist

Performed checklist from memory or omitted checklist, missed items,

performed late or at the wrong time.

Documentation

Wrong weight and balance, fuel information, ATIS, or clearance

recorded, misinterpreted items on paperwork.

Other procedural

Other deviations from regulations, fight manual requirements or

standard operating procedures.

Communication Errors

Pilot to external

Missed calls, misinterpretation of instructions, or incorrect read-backs to

ATC, wrong clearance, taxiway, gate or runway communicated.

Pilot to pilot

Internal crew miscommunication or misinterpretation.

UAS (UNDISERE AIRCRAFT STATE)

Undesired aircraft states (UAS) are pilot-induced aircraft position or speed deviations, misapplications of fight controls, or incorrect systems configurations associated with a reduced margin of safety.

For a safe flight, we must quickly recognize and recover from an undesired aircraft state before it leads to a loss of control or an uncontrolled flight into the terrain.(CFIT: Controlled flight into terrain)

Examples of errors and associated undesired aircraft states in charter operations include:

Mismanagement of aircraft systems (error), resulting in aircraft anti-ice not being turned on during icing conditions (state).

Inappropriate scan of aircraft instruments (error), resulting in an unusual aircraft attitude (state)

Flying a final approach below the appropriate threshold speed (error), resulting in excessive deviations from specified performance (state).

Examples of Undesired Aircraft States

Aircraft handling

Vertical, lateral, or speed deviations

Unnecessary weather penetration

Unstable approach

Long, foated, from or off-centreline landings.

Ground navigation

Runway/taxiway incursions Wrong taxiway, ramp, gate, or hold spot Taxi above speed limit.

Incorrect aircraft configuration

Automation, engine, flight control, systems, or weight/ balance events.

Applying TEM and Countermeasures

TEM involves anticipating and calling out potential threats and errors as well as planning countermeasures in the self-briefing process at each stage of the flight to prevent threats and errors from becoming an undesired aircraft state. This needs to be done in a structured and simple way, without becoming complacent about commonly encountered threats such as weather, traffic, and terrain.

There are three kinds of countermeasures:

Planning countermeasures including fight planning, briefing, and contingency planning.

Execution countermeasures including monitoring, cross-checking, workload, and systems management.

Review countermeasures including evaluating and modifying plans as the fight proceeds, and inquiry and assertiveness to identify.

Once you recognize an undesired aircraft state, you must use the correct countermeasure rather than fixate on the error and address issues in a timely way.

Error Management

By acknowledging that errors will occur, we change our focus from error prevention to error recognition and management. Because unmanaged or mismanaged errors may result in an undesired aircraft state we need to be constantly alert to recognize and fix them early.

Once you recognize an error, it is important you focus on managing any resulting undesired aircraft state. In trying to manage an error, we can become fixated on its cause and forget firstly to ‘aviate, navigate and communicate’.

For example, if you become uncertain of your position, you need to make a timely decision to perform a ‘lost procedure’. You may be tempted to ascertain why you became lost and blunder regardless (undesired aircraft state), rather than initiating a logical procedure to re-establish your position, seek assistance from other aircraft or ATC, or plan a precautionary landing.

While the basic concept of TEM is simple, including it in your standard practices is more challenging. But if you do, you will see the benefit of a planned and structured approach to staying ahead of the aircraft and staying safe.

So, how do you prevent errors from multiplying and putting you in an undesired aircraft state? In this case, a go-around would have provided time to get everything together and sort things out.

Consider how you could have anticipated and briefed yourself on the threats and errors on this day and the countermeasures that you could have put in place to manage the situation and avoid an undesired aircraft state you couldn’t control.

Assessing the application of TEM

Maintains effective lookout

Maintains situational awareness

Assesses situations and makes decisions

Assesses solutions and risks

Sets priorities and manages tasks

Maintains effective communication and interpersonal relationships

Recognises and manages threats

Recognises and manages errors

Recognises and manages UAS

KEYPOINT

The threat and error management (TEM) approach recognizes that making errors is a normal part of human behavior that can and should be managed. It promotes a philosophy of anticipation or ‘thinking ahead’.

The three basic components of the TEM model are threats, errors, and undesired aircraft states (UAS). Crews must know when to switch from error management to undesired aircraft state management.

Pilots who develop strategies or countermeasures such as planning, and review or modification of plans, tend to have fewer mismanaged threats, commit fewer errors, and have fewer undesired aircraft states.

Comments